The day didn’t announce itself so much as it unspooled—quiet as a ribbon, soft as the inside of a seashell. Light slid through the slats of the fence and scattered across the grass, catching on dew like a thousand tiny mirrors. Somebody laughed in the distance—one of the cousins, probably—and somewhere a wind chime found a rumor of a breeze and made a sound like a memory you couldn’t quite place. There was lemonade clinking in tall glasses. There was music from a speaker no one could see. There were the smells of charcoal and rosemary and peach cobbler cooling on a sill. It could have been any afternoon from any summer. It could have been the start of one of those days that leaves you tender with nostalgia and nothing else.

I stood at the edge of my parents’ yard and watched the long shadows trade places with the patchwork of light, watched the smaller kids thrum around the old oak like planets around a sun. Emma had found a corner of quiet near the perennials—her favorite kind of corner—with her knees tucked under her and her lips moving as she whispered a storyline into a toy’s stitched ear. She does this: builds whole universes out of breath and imagination, and then she lets you in like you’re lucky to be invited. Six years old and already the curator of a small, brave world.

I thought about going over. I thought about letting her be.

“Sarah,” Aunt Linda called, dropping her sunglasses down her nose, “you simply have to see the photos from Cape Cod. I swear, those dunes look airbrushed in real life.”

I smiled, came when I was summoned, nodded in all the right places. And still—half of me stayed tethered to the edge of the yard where my daughter’s fingers worried the satin ear of a plush unicorn and her mouth tried on voices for a story only she could hear. If you’d asked me then what needed guarding, I wouldn’t have said “everything.” I would have said “nothing.” I would have said “we’re fine.”

It is a strange, devastating thing to learn in a single afternoon how wrong you can be.

1) The House That Favorites Built

The thing about my family is that the stage is permanent. Even when the props change, even when the cast pretends to rotate, the lead roles are fixed. My mother sits in the lawn chair that functions as a throne, and my older sister, Madison, occupies the space beside her the way sunlight claims the sill—naturally, confidently, as if the sill existed strictly for the sun.

Madison was born with applause braided into her hair. She was the honor-roll, homecoming, head-turning version of girlhood my mother could hold up like evidence that she’d done something right. And I—two years behind, messy and bookish and earnest in the wrong ways—could not be shaped into satisfactory proof. It wasn’t a secret. It was a climate. You learn to breathe it or you suffocate.

Most of the time, I breathe it. I make a polite face. I pack a Tupperware with the last of the potato salad even when Mother says, “Leave that, darling; Madison will take it.” I tell myself I am grown and that being grown means I don’t need what I never got. It works until it doesn’t.

On that particular Saturday, the yard had been dressed as if for a magazine—string lights, gingham, platters, a stack of paper napkins with embossed gold leaves. My father wielded a spatula dutifully. He is a man who turns pain into projects. Give him a rotten board and he’ll replace it. Give him a grievance and he’ll sand it into silence.

“Perfect day,” he said to me as he aligned the hot dogs with the accuracy of a surveyor.

“Perfect,” I said back, because that was the role I knew.

Madison arrived with Olivia—nine years old and lacquered in the confidence you get when adults orbit you. Olivia has the kind of halo people mistake for promise. Maybe it is promise. Maybe it’s something else. She beelined through the crowd like a girl who has never once believed she should wait to be offered anything.

“Hi, Aunt Sarah,” she sang, already looking past me. “Where’s Emma?”

“By the flowerbeds,” I said, and the smallest warning bell tinked in the corner of my mind. Not an alarm. Just a suggestion of potential weather.

“Don’t worry,” Madison murmured as she brushed by me, the sleeves of her linen blouse whispering that expensive whisper. “Olivia is getting so much better at sharing.”

That was a curious sentence—you learn to hold these little curiosities up to the light, like marbles. Better at sharing, the way you’d say it about a child who must be coaxed into generosity as if generosity were a bitter pill. I let it roll to the back of the drawer with all the other curious sentences we keep when we’re too tired to ask for clarity.

Aunt Linda swiped her screen to the next sunset. “Look at the color,” she said. I said “oh, wow,” exactly on cue. Behind us, above the low hum of family, a laughter I know too well struck a higher note—my mother’s delighted cackle. I didn’t turn around. I didn’t want to know what joke I had failed to be part of.

In the corner, near the coneflowers, Emma kept whispering the United Nations of voices her toy demanded of her: a fairy, a horse, a brave sister, a dragon who wasn’t so bad once you learned about his allergies. The unicorn, like always, played the part of witness. It has a rainbow mane Emma smooths flat with concentration and love. It is stitched in a way that looks simple until you look again and realize how much care was required to make it look that way.

Her late grandmother on her father’s side—David’s mom—had given it to Emma the year she died. “Something to hold when I’m not around,” she’d said, with the gentle humor of people who know how leaving works and wish it were different. She’d smelled like gardenias and cinnamon. Emma remembers the smell more than the shape of the memory. The unicorn remembers both.

I should have known better than to bring it to a house where favorite is a job description and scarcity is a sport. But even mothers who know better get tired. Even mothers who map the minefield sometimes miss the newest hole in the ground.

2) What a Child Knows

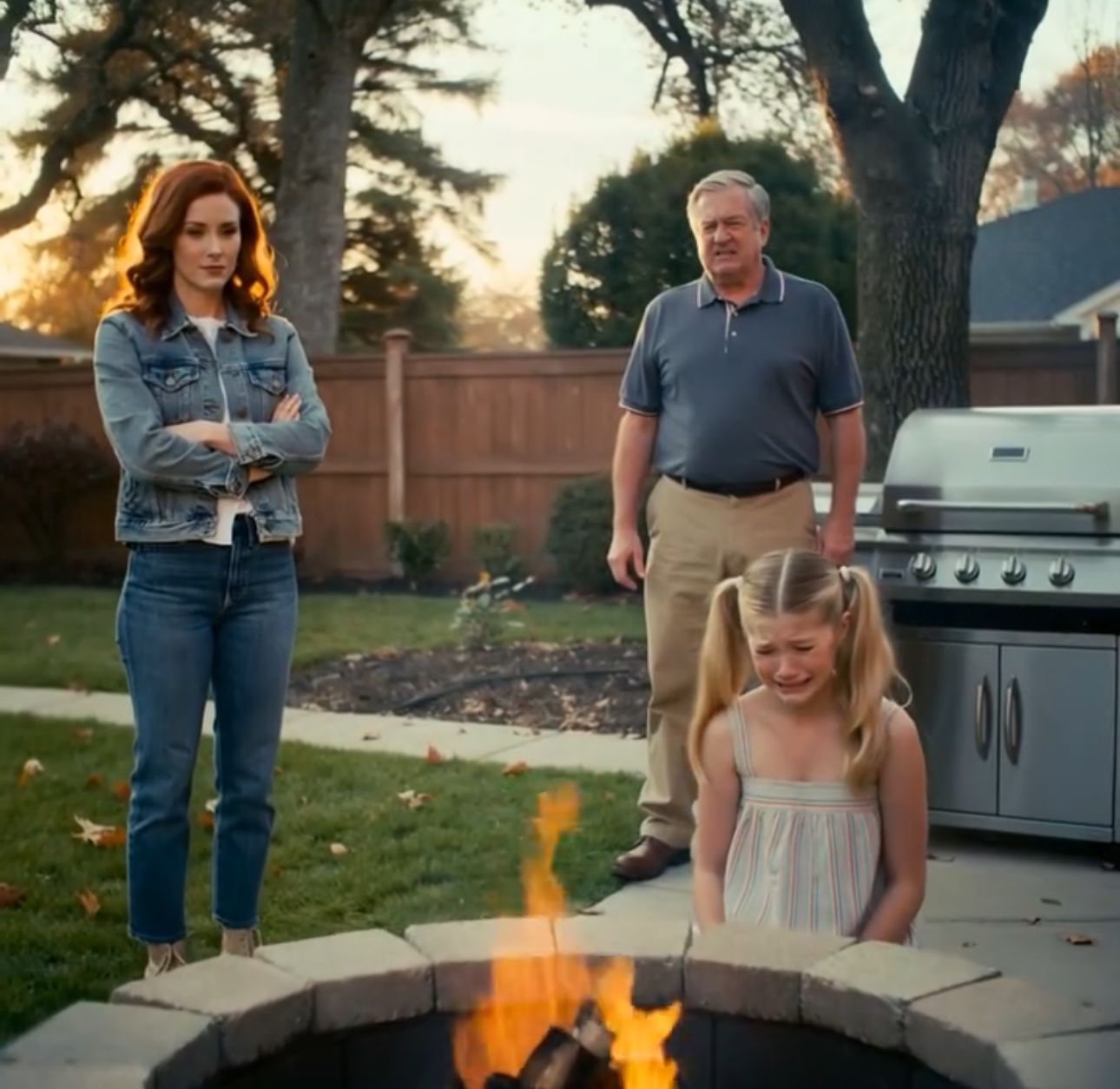

It takes a particular kind of bravery to approach your mother with your whole face wet. Emma ran the length of the yard with her fists clenched and her mouth a thundercloud and still—she did not drop the unicorn. When she collided with my knees, the impact lifted dust and the scent of cut grass, and her words came ragged, each one vaulted over a sob the way a deer clears a fence.

“She—she says—it’s hers—she wants it—Mommy, tell her—tell her to stop—tell her to stay away.”

She referred to Olivia with the bright generic of a child still learning the grammar of kin: my niece. Children map the world with relational math: this is mine, this is yours, this is ours. They have rules about fairness no one taught them explicitly. When they bring those rules to you, they expect you to enforce them with the solemnity they deserve.

I wrapped my arms around Emma and felt her heart beating like a startled bird. “Sweetheart,” I said, wiping her cheeks with my thumbs, “you don’t have to give anyone something that’s special to you.” It felt brave to say out loud in this backyard. It felt like treason and truth.

And then, cutting the light like a blade, came my mother.

“What did she just say?” The tone was a familiar one—silk threaded with steel. There are tones that drag you back by the hair to kitchens where you are ten and whatever you are saying is automatically wrong.

“She’s upset,” I said, standing. “Olivia wanted her toy, and Emma said no.” I kept my voice level, kept it for Emma, who had pressed her face into my stomach and wrapped the unicorn in the canyon of her arms.

“You’ll give that to your cousin,” my mother told Emma, the way a judge passes sentence. She did not crouch to meet Emma’s eyes. She did not ask permission to enter this moment. She simply swiped at it as if erasing a stray pencil mark.

“No,” Emma whispered, so close to my shirt that the word warmed the cotton.

I opened my mouth to say This is not the place, not the way. I opened my mouth to say Start with please. I opened my mouth to say She doesn’t have to. I don’t know what I might have said, because my mother decided to empty the scene of language altogether.

She lunged. Quick, like she had practiced speed in a mirror. She caught the unicorn by its pastel belly and yanked. The grip was so sudden Emma stumbled backward and let out a sound I have heard only once—then—and hope never to hear again. She made the sound of some animal inside her realizing the world is not what it believed.

“Mom!” I said, reaching, but my mother had already turned toward the firepit where my father had coaxed the last of the weeds into drowsy ash. Flames licked low and lazy at the mouth of the stones.

“What are you doing?” I asked, even though my body already knew. Even though my body was already moving. The moment stretched the way a rubber band stretches right before it snaps.

“This’ll teach her about sharing,” my mother said, sing-song and cruel, and dropped the unicorn into the orange mouth of the afternoon.

Plastic has a particular smell when it remembers it used to be something else. The mane curled on itself, the eyes-blown-glass went blind, the belly caved as if with grief. The rainbow went to smoke. The unicorn made no sound because of course it did not; it had always relied on Emma for its voice.

My daughter screamed. She screamed as if her small chest contained an ocean that could be emptied. She screamed as if screaming were the only language left when the adult world shrugs and calls what it wants justice.

I reached for a stick, a pot, anything with a length I could trust not to burn my skin, but there are some undoings you cannot undo with heroics. Some moments are made to be survived, not fixed. And anyway—before I could even bend, my mother turned in a clean arc and slapped Emma across the face.

The sound—a bright, obscene punctuation—tore the music out of the yard. Emma’s head snapped to the side. Her knees went out. She was suddenly smaller, all the blood fled to shock, and her hand flew to her cheek with the kind of protective reflex a child shouldn’t possess.

“Don’t you ever disobey your cousin,” my mother said, standing over my daughter as if she were lecturing a class. “Whatever she wants, you give her.”

There are things you imagine you might do in a moment like that—throw yourself, scream until the air learns your name, lift a house off its foundation with your bare hands. The truth is simpler: you move. I moved. I put myself between my daughter and my mother and I gathered Emma up as if gathering were an answer. She was shaking, and her tears had given up forming drops; they came in a sheet.

“What is wrong with you?” I asked my mother, and I meant it—not as an insult, but as a diagnosis. In my periphery, a chorus of relatives remembered their phones, their cuticles, the surface of a potato salad. My father looked at the grill like it contained an emergency he alone could solve by turning something over.

“She needs to learn her place,” my mother said, and a lifetime of rooms rearranged themselves inside me. “Olivia wanted that toy. You give your family what they want.”

“It didn’t belong to Olivia,” I said. “That toy was from Emma’s other grandmother. The one who died. It was the last thing she had that smelled like her.”

My mother shrugged like grief was a foolish hobby. “Just give me the money and I’ll buy my precious granddaughter a new one.”

“Absolutely not,” I said, and my voice shook so hard the syllables jangled into one another. “You just set my child’s comfort on fire and hit her. And now you’re asking me to finance your cruelty?”

“Get out,” my mother spit, the words frothing at the edges. “Get out of here, right now.”

Madison crossed her arms behind her like she was standing for a portrait. “You heard her. Poor Olivia is traumatized watching your daughter throw a tantrum.” Her smile was a paper cut.

I looked around, at the men I had called uncle my whole life, at the women who had pressed bobby pins into my hair and love into casseroles, at cousins who’d built forts with me out of moving boxes. Every eye slid off mine. Not one person said This is wrong. Not one person moved to lift my daughter up beside me and build a wall of bodies against this. In the end, I was the only wall she had—and that would have to be enough.

I walked to the car. I did not run. I did not give them a story they could call drama. I strapped Emma into her seat and watched her small hands shake as they clutched air where a unicorn used to be. She finally whispered, “Mommy, why does Grandma hate me?” and I broke in the quiet, in a way you cannot hear but can feel, like a rope surrendering to a new law of weight.

3) The Hours That Decide You

Grief makes a noise even when you try for silence. It creaks the floorboards and steams the mirrors and shoves its shoulder against the closed door. That night, Emma cried until her body tired of the salt. She threw up once, from a sorrow that looks for any exit it can find. I held her hair, renamed my anger into steadiness because she needed steadiness. When sleep finally took her, it did it warily, as if sleep itself were afraid to be in the room.

I cleaned up the small, terrible mess and then I sat at the kitchen table and turned the house lights on like a stage manager who understands the show is over and what’s left must be sorted. On the table I put a notebook, my phone, a glass of water gone warm. I wrote down every detail: time, words, the slap, the heat of the fire, the shape of the mark on Emma’s face. I took photographs of that mark from every angle the light could offer. I snapped a picture of the clock as proof of when. I made a list of witnesses as if making a list could make them brave tomorrow. I scrolled the family group chat and documented my sister’s attempt at spin:

So sad that Sarah couldn’t handle Emma’s tantrum today. Mom was just trying to teach her about sharing and Sarah completely overreacted. Some people aren’t cut out for family events.

Aunt Linda’s sad-face emoji might as well have been a novel. Cousin Mark wrote, Some people are too sensitive. My father wrote nothing at all.

There is a moral moment in every family story where you decide whether you will keep the great secret going. I didn’t ask for that moment. It came, anyway. I could hear my grandmother’s voice in my head—my father’s mother—who said the thing nobody else in the room would say, every time she ever needed to, and paid for it with exile. I decided in that chair, under that light, to pay whatever it cost.

I called Rachel Martinez, my divorce lawyer. She is the sort of woman whose sentences end with outcomes.

“Tell me everything,” she said, and when my throat gave out halfway through the slap she let me breathe and begin again.

“This is assault on a minor,” she said when I finished. “I want the photos, the written account, the names of everyone present, the screenshots. I’ll file first thing Monday. Sarah—do not doubt me. This is criminal. If you need permission to be furious, I grant it.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it. “I don’t want to be the girl who keeps the family’s secrets anymore.”

The next call was to David, my ex-husband. We became very good at being divorced. We co-parent like people who agree on the price of sleep and the sanctity of gentle voices.

“Is she okay?” he asked, sleep in his voice.

“No,” I said. “And you need to see it with your own eyes.”

He came in twenty minutes, hair wild, sweatshirt backward. We stood at Emma’s door and watched her mouth beat a rhythm against whatever dream held her. He looked at the photos I’d taken and the quiet in him turned to a clean, useful rage. “I never liked your mother,” he said, “but I never imagined this. What do you need from me?”

“Be my witness,” I said. “To the bruise on her face, to the way she sleeps, to the way her breath catches when she rolls over. And tomorrow we get her seen by her pediatrician so this has a name in a file that isn’t mine.”

“Done,” he said. He meant it. He stayed and we each wrote a statement of the night from our own corners of the table like a pair of carpenters building the same cradle. When he left, he kissed Emma’s forehead with the sort of carefulness you put on someone you know is breakable.

At night I remembered other nights. I remembered being seven, and my mother tossing my favorite doll in the trash because my dress had grass stains. I remembered being twelve and being told I was getting a belly, that no boy would love a brainy girl. I remembered being sixteen and being informed that girls who spoke their mind ended up alone. I remembered being twenty-three and newly pregnant, and my mother saying, “At least you finally did something right, even if you couldn’t keep your husband interested.” I remembered each sentence and realized they were not sentences: they were mortar. A sick kind of house had been built around me all my life and I had called it weather. That night, I called it a house. And houses can be left. Houses can be gutted and rebuilt.

I pulled the journals from my closet—the ones where younger versions of me told the truth to paper because paper was the only thing that didn’t flinch. I photographed entries that proved the pattern: the favoritism, the thefts of small joys, the way my mother always transmuted love into compliance.

By sunrise, a thick folder sat on the table. Paper can’t protect a child’s cheek. It can, however, tell a story a judge cannot ignore.

4) Naming Bruises, Naming Boundaries

Dr. Chen wears her empathy like other doctors wear their stethoscopes. She took one look at Emma’s cheek and her mouth made the shape of a word she did not speak. She knelt to Emma’s height and asked questions like they were soft stones. She documented the bruise, pressed as gently as possible, and entered the official phrases into the record: contusion consistent with adult hand strike, facial tenderness, acute emotional distress.

“I’m required to report suspected abuse to CPS,” she said to me, her voice a careful place.

“Please do,” I said. “We aren’t hiding.”

She wrote a referral to a child psychologist, the ink decisive, the handwriting calm. “Early intervention matters,” she said. “And I know a therapist who treats grief as part of trauma, which seems appropriate given the toy’s origin.”

From there, Rachel’s office. We sat with coffee we did not drink and turned paper into motion. Restraining order. Police report. Photocopies of the bruise. List of witnesses. Timeline. Rachel’s jaw is a geometry of justice when she’s working. “This will get loud,” she said. “Your mother will call it betrayal. She will try you in the court of family.”

“I’ve already been tried there,” I said. “By a jury of people who refused to look up.”

The restraining order was served two days later. My father called that night, his voice a thing that had learned humility late in life. “She screamed the whole time,” he said. “She told the officer you were ruining the family. He told her to lower her voice or he’d arrest her for violating the order mid-scream.” He cleared his throat. “I should have stopped her. I should have stopped so much.”

“I need you to testify,” I said. “Not for me. For Emma. And for the part of you that knows the cost of your quiet.”

After a long silence, he said, “Yes.”

The CPS caseworker, Teresa, sat cross-legged on our rug and looked Emma in the eyes. She had a gift for making the room feel like it belonged to the child. She interviewed us separately, spoke with David, with Dr. Chen, with Emma’s teacher. Her report, later, was mercifully adult and boring, which is how the truth should look on paper: the child experienced physical harm from maternal grandmother; evidence supports emotional abuse pattern in the extended family system; protective parent is engaged and appropriate; recommend no unsupervised contact with the grandmother; consider ongoing therapy.

If the story had ended there—with the order, the report, a no-contact boundary—I would have been grateful. But families are systems, and systems hide losses that have nothing to do with toys. It’s remarkable what assaults come to light when you finally turn every lamp on.

5) Following the Money, Following the Lies

The house my mother ruled from belonged to a trust originally built by my father’s mother, my grandmother, whose love language was careful planning. The trust was designed like a fence around a garden: flowerbeds labeled, gates locked, harvests to be shared by grandchildren when time ripened each piece of fruit.

My mother was made trustee against my grandmother’s better judgment—my grandfather insisted—and the trust included a host of guardrails: quarterly accountings, multiple signatures for major transfers, distribution only when the youngest beneficiary reached thirty. In theory, it was idiot-proof. In practice, idiot-proof isn’t narcissist-proof.

I remembered papers I’d signed four years earlier, mid-divorce, mid-toddler-meltdown, when my mother had said, “Just routine maintenance for the trust, dear, nothing to worry about.” So I went to the county recorder and asked for copies. The clerk printed deeds and transfers, her eyebrows climbing as she spread the papers like a card trick.

“This property shows a transfer from the trust to… your sister,” she said, tapping the date. “But the trust shouldn’t distribute yet.”

“That’s my signature,” I said, pointing to the loopy S I’ve been writing since eighth grade. “Except I never read this. I never would have agreed to that.”

“Talk to an estate attorney,” the clerk advised, and circled the number of a man who had retired and then un-retired because boredom didn’t suit him.

Bernard Whitmore smelled like peppermint and righteous anger. He had drafted the original trust. When he saw the papers, his eyes went flat and fierce. “Your grandmother begged me for mechanisms,” he said. “She did not trust your mother. I gave her mechanisms. It seems your mother found bolt cutters.”

He referred me to Patricia Chang, a forensic accountant who treats money trails like crossword puzzles she intends to finish in pen. Patricia and her team waded into bank records, receipts, rental ledgers. They called contractors whose invoices had fed “urgent repairs” on properties that looked unchanged since 1998. They matched social media photos of my mother’s vacations with unreported withdrawals. If the devil is in the details, Patricia greeted him by name.

Fifteen years of embezzlement. Nearly a million siphoned: rental income pocketed, forged signatures on transfers, fake expenses paid to companies that didn’t exist, assets liquidated under the table—jewelry, paintings, antique furniture—my grandmother’s care packaged into lies. The ledger wasn’t a ledger. It was a confession written in numbers.

“The IRS will want to see this,” Patricia said, sliding a drive across her desk. “She’s been filing modest returns while living beyond them. That’s how we catch them, you know. They think the government is as bored as their family is.”

Marcus Thompson at the IRS was not bored. He reviewed Patricia’s audit like a man offered a second cup of coffee after a long night. “We flagged her years ago,” he confessed, “but suspicion is not evidence. You have given us so much evidence we might drown in it.” He explained penalties, interest, the possibility of jail, the predictability of fines. He explained that numbers have a way of telling the truth even when people insist on lying.

Meanwhile, I followed a parallel trail to my sister. “Madison’s Lux Finds,” her online boutique, always glittered suspiciously. She bragged about five-figure months and then claimed a near-empty profit on tax returns I’d glimpsed when my father asked me to help him eject a stuck print job from his ancient printer. I documented her posts—sold out in two hours!!—and laid them beside bank deposits that didn’t show up on filings. Former employees confessed the off-books cash sales and the inventory purchased with “Mom’s connections.”

An anonymous tip to the state tax board—with screenshots, statements, and a neat list of suppliers—set another bowling ball rolling down another lane. “Filing false,” the investigator warned, “is a crime.” “So is stealing,” I said, and walked my calm out the door.

These things don’t topple overnight. They teeter. They groan. And then one day they go like a chimney somebody forgot to brace. My mother shrieked. Madison posted their version of events on Facebook, all shining teeth and martyrdom. But the math didn’t care about their adjectives.

6) The Meeting Where Nobody Blinked

Before the courts and the auditors rounded the last corner, I did something my mother underestimated: I called a family meeting. She assumed control of meetings the way a queen assumes the throne. I rented a neutral conference room and hired a court reporter. I used my father’s email—he asked me to; he wanted the blast to come from his address to guarantee attendance—and typed the words mandatory for all beneficiaries.

They came because money teaches obedience.

My mother walked in with Madison as if entering a garden she owned. She wore a dress she saved for victory. She sat at the head of the long table without being invited, because invitation is a language she never learned.

“Let’s make this quick,” she said, tipping her chin. “I have a hair appointment.”

“It won’t be long,” I replied, standing with Rachel beside me like a pillar. We had copies. We had receipts. We had notarized statements and a forensic audit bound with the ugliness of truth.

“Your grandmother’s trust,” I started, “was designed to protect her grandchildren. Instead, it became a personal checking account for two people.” A murmur moved through the chairs. Papers flipped. Throats cleared.

“This is ridiculous,” my mother tried, but Uncle Richard—my father’s younger brother who became an accountant as if accounts could rescue him—spoke from the corner. “It’s not ridiculous,” he said. “It’s accurate.” He passed me a thick folder. He had been quiet all my life—complicit, frightened, cornered by a youthful mistake my mother had blackmailed him with—and now he was done being furniture. He had kept everything. Copies of checks. Spreadsheets of cash “repairs” that never repaired anything. Notes my mother wrote to herself about “borrowing” from beneficiaries she called ungrateful behind their backs.

My cousins read and forgot to breathe. My aunts cried with the quiet of women who recognize a terrible pattern and add their own missing pieces to the mosaic. My father looked down at his signature—reproduced at the bottom of a transfer he had never signed—and went white. The court reporter’s machine clicked like rainfall.

“You can’t prove—” Madison began, and Rachel raised a hand.

“We can prove embezzlement,” Rachel said, calm as a ledger. “We can prove forgery. We can prove theft of estate assets. We can demonstrate tax evasion with a timeline the government finds compelling. We have an independent forensic accountant’s report. We have witnesses. We have your uncle’s records. We have the trust’s original attorney ready to testify. We have enough to make this room spin.”

“This is betrayal,” my mother whispered, her voice suddenly small, and I remembered the unicorn, and I let the word pass over me without landing.

“This is accountability,” I said. “Also: Emma and I have a restraining order against you. CPS has documented the assault. This—” I held up one more piece of paper— “is a transfer of fifty thousand dollars from the trust to Madison’s personal account marked ‘loan’ without documentation. Tell me about the interest rate, the repayment schedule, the collateral.”

Silence is honest. For a full minute, nobody tried to shape the air into a lie.

“I’m giving all of you a choice,” I told the room. “Join me in making this right or stand in the way. The courts are coming either way.”

“I’m in,” my cousin Jennifer said, standing like she had grown six inches during the meeting. “My mother died believing she left me something. She didn’t leave it to Madison.”

Others nodded—voices unspooling, pipes finally cleared. In the end, the only two left without chairs to sit on were my mother and Madison, who swept out together, trailed by their final shared delusion. At the door, my father intercepted my mother and quietly, efficiently, handed her divorce papers. She looked at the envelope like it contained climate change. She took it anyway.

7) The Difference Between Noise and Justice

Then came the months you might consider boring if you have never needed paperwork to save you. The restraining order held. The forensic audit rolled through probate like a flenser’s knife. The IRS smiled with the patience of a predator that doesn’t need to chase. The state tax board took Madison’s boutique apart down to its last shipping label. The court removed my mother as trustee and froze the trust. An independent trustee took over and treated the accounts like a recovery room. The houses were appraised, sold, proceeds held while restitution was calculated. The jewelry my grandmother loved was traced, cataloged, searched for. Some pieces turned up in pawn slips, some in a neighbor’s safe, some—lost forever—existed only in photographs and affidavits.

Criminal charges were filed. My mother pled to avoid prison; she couldn’t bear the idea of orange not matching her blush. Five years’ probation. Full restitution. Community service at a charity she’d mocked for decades. Madison signed a similar deal. They paid back what they could, paid fines, paid with their names in a public record that did not use the words generous or misunderstood.

The family broke and then reassembled itself with empty seats left for those who preferred the old order. Those of us who remained were tender in a new way, like scar tissue you press with a thumb to test if feeling has returned. It had. Feeling had returned.

My father, humbled by his own absence, learned how to show up. He took therapy like penance and found, somewhere in the middle, an honest desire to be different. He wrote Emma a letter that began, I am sorry I did not protect your mother when she was you, and ended with, I will spend the rest of my life making sure you are safe from the kind of love that is actually control. He bought Emma a new unicorn—not to replace the lost one (nothing replaces the smell of gardenias and cinnamon), but to gesture toward a promise. They put it on a shelf together. It watches over plastic horses and the cardboard castle Emma built from a shoe box. It is not a talisman. It is a companion.

Madison took a job with a name-tag. It suited her less than she believed the world owed her. Olivia started therapy too. Somewhere in there, a child who had been told she was owed the sun learned that light belongs to everyone who stands in it. It is possible to wish grace for a child whose mother taught her the wrong arithmetic.

As for the trust’s money, none of it felt triumphant. It felt like right sizing. We put Emma’s portion into a fund that will become a future she chooses. With mine, I did two things my mother would call showy: I wrote a check to a nonprofit that creates memory kits for grieving kids—shadow boxes and journals and plush toys engineered to hold scent—and I started a small foundation in my late mother-in-law’s name to provide therapy grants for children navigating loss and complicated families. I can’t make plastic un-melt. I can make other kids feel less alone while they learn that what smells like their grandmother can live in a box and in the soft fur of a toy and also in them.

8) The Long Work of Peace

Children heal on timelines that have more to do with songs and fewer to do with calendars. Emma’s nightmares dwindled, then flared, then dwindled again. Sometimes she woke and named fire. Sometimes she woke and only needed water. Dr. Alvarez, the therapist Dr. Chen recommended, taught Emma to find a safe place in her head and decorate it—pillows, a window, a unicorn that does not burn. She taught me how to sit beside those decorations and not rearrange them to suit my taste. That is a discipline I intend to practice until I’m old.

At school, Emma drew a picture of a dragon who learned not to breathe fire on the things other people loved. The dragon had a very small crown. It was a good drawing.

We built Saturdays around pancakes and library trips. We built Sundays around whoever loves us with no performance required. Family still exists for us—just smaller, kinder, chosen. At gatherings now, there are no thrones disguised as lawn chairs. There are quilts where everyone sits with their knees touching. There are kids who pass a stuffed animal around because they want to, not because they must. If a child says “no,” the adults nod like the word is a treasure.

I see my mother sometimes, but only in rooms with a judge and a court reporter or by mistake on the local news when they cover community service and someone pans past her face. She sent a card through a friend for Emma’s seventh birthday—fifty dollars and I’m sorry in her handwriting, which looks like a caged song. We returned it with a note that said, We don’t accept apologies that cost us again to receive. Boundaries are not only lines you draw; they are letters you send back unopened.

The last time I saw her up close was at the final restitution hearing. She sat three rows ahead, smaller than she has ever allowed herself to be. You expect to feel something at the sight of a toppled monument. I felt nothing but relief, the kind that fills your chest without adrenaline. It is possible to be done without being mean about it. It is possible to stop performing for people who only clap when you bleed.

When we left the courthouse, the sun turned the concrete into warmth and Emma reached up and found my hand. “Can we get ice cream?” she asked, like justice should always be followed by sprinkles. “Absolutely,” I said, and if you’d told me three years ago that this would be victory, I would have wanted something flashier. But joy is quiet work. You swing your feet from a bench and watch pigeons practice their meetings and your child tells you about a science experiment with vinegar and baking soda like it contains secrets about the universe. Maybe it does.

9) What I Did Next

People who loved the old order ask me, sometimes with a mix of awe and accusation, What did you do next?—as if I must have set the house on fire literally, as if consequences only count if they explode.

Here is what I did: I stopped being quiet. I stopped making myself small in exchange for a seat at the table where I was served contempt. I stopped translating cruelty into “family” for my daughter’s sake. I documented. I called people whose job it is to believe evidence. I chose the long, boring corridors of the law over the short, dramatic hallway of a screaming match. I wrote checks to children who understand the smell of a grandmother better than most policemen and better than some mothers. I told the truth every time I was asked, even when my voice shook, even when the court reporter’s keystrokes made me feel like I was carving the words into something harder than paper.

I burned nothing except the script. And because the script was the thing that told us who was allowed to be loved, burning it was the only fire anybody needed.

One afternoon last month, Emma asked from the back seat if forgiveness means letting people do the same thing to you again. She is nine now. She can braid her own hair badly and she can name her feelings properly and she still likes to read out loud to her stuffed animals in a lineup.

“No,” I said. “Forgiveness sometimes means setting the table in your heart and saving a chair for peace. It never means putting your cheek out for the same hand.”

She thought about that and then said, “Can we save a chair for Grandma Grace?”—my former mother-in-law. And we do. We saved it the way you save things that make life warmer: carefully.

The unicorn on Emma’s shelf has a tag with Grandma Grace’s name on it. Sometimes Emma pulls the toy down and presses her face into it like she can harvest a smell that exists mostly in the architecture of her heart. She always smiles after. “Still there,” she says. The thing about love is that when it is real, heat doesn’t melt it; it moves.

I tell Emma at least once a day, and more when the world is unkind: “You are worth protecting.” She has begun to say it back to me. The other night, when I was wrestling a jar of pasta sauce that wouldn’t give, she said, “You are worth protecting, Mommy,” and took the jar and banged its lid on the counter with a confidence I recognized. The lid released the way old rules do when you introduce them to a new generation.

So—what did I do next that left them speechless? I chose us. I chose consequences over composure, peace over performance, truth over the version of love that comes with terms and conditions written in invisible ink. I chose to raise a child who will never believe that her safety is negotiable or that toys are more precious than people or that blood is a magic trick that absolves harm. And then I ate ice cream with her on a bench outside a courthouse while the pigeons discussed theology at our feet, and we laughed about how vinegar makes baking soda grow a volcano, and we went home to a small house where the only throne is the couch and the only crown is the one a girl draws for herself in crayon.

If you need drama, here is the drama: a kingdom toppled simply because we stopped bowing. A grandmother ordered by a judge to return money she pretended was hers. A sister learning to count in honest digits. A whole branch of a family, once trained to confusion, now fluent in the word enough.

And if you need an ending, here is one I choose: Sunday morning, my daughter asleep in the bed she picked for herself, the sunlight doing that gentle lattice-work across her blanket, the toy unicorn looking ridiculous and perfect on the shelf; coffee burbling; my phone silent; the knowledge that if anything comes for us, it will find a door locked by law and love and the kind of mother who would pick up her child and leave a yard full of people rather than ask that child to endure one more minute of training in the wrong kind of love.

I have learned this: some family gatherings are not gatherings. They are auditions. We don’t audition anymore. We don’t impress. We belong to the rooms we build—rooms where no one laughs while a beloved thing burns, rooms where no one tells you to hand over what you love in exchange for a cheaper peace, rooms where the first rule is simple and the last rule is the same: we do not hurt each other here.

If you’re waiting for thunder, I can’t give you that. What I can offer is a quieter miracle. A child who sleeps all the way through the night. A bruise that faded. A mother who learned that her voice can be used not as an alarm but as a lullaby. A ledger corrected. A house sold. A check cut to a charity that puts a memory into the hands of a small person and says, Hold this. You’re allowed.

And the unicorn? There is a rumor in our house that sometimes, late, when the air conditioner hums just right and the wind hits the window the way it used to, the unicorn’s rainbow mane catches the light and glows like it remembers something. Emma swears she saw it once. I didn’t doubt her. Some things survive the fire by becoming light.